In a nutshell

- 🧠 Overhydration (hyponatraemia) dilutes blood sodium, drives cellular swelling—especially in the brain—and can escalate from fogginess and headache to seizures.

- 🔎 Early clues include crystal‑clear urine, frequent night-time wees, puffiness, nausea, and cramps; dark urine suggests dehydration, but clear urine plus headache can signal overhydration.

- 🚨 Red flags—worsening headache, repeated vomiting, confusion, seizures, breathlessness—require urgent help (call 999); share how much and how fast you drank, the fluid type, and any medications.

- 💧 Safer hydration: let thirst guide, aim for pale straw urine, include electrolytes for long or sweaty efforts, drink roughly 400–800 ml/hour in endurance, and avoid routinely exceeding ~1 L/hour.

- 👥 Higher-risk groups: endurance athletes, festival-goers using MDMA, older adults, and people on SSRIs/diuretics or with heart, kidney, or liver disease—who may need personalised plans.

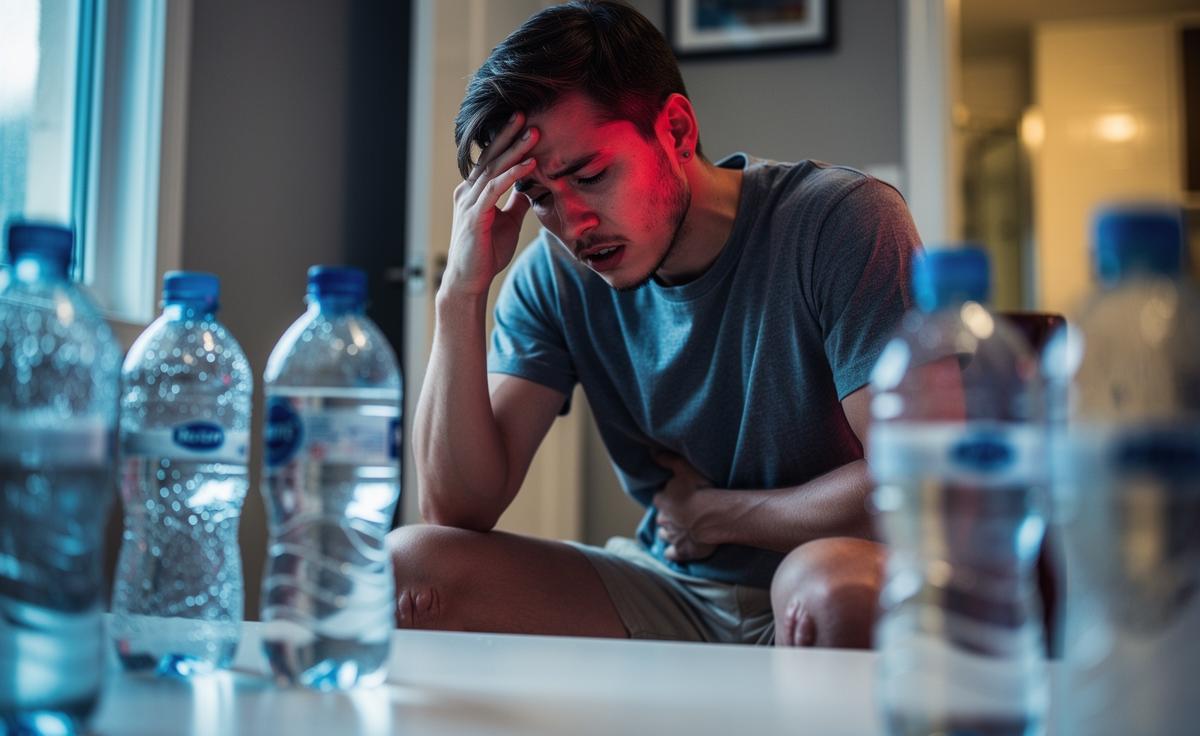

We’re told to drink more water, to carry bottles everywhere, to top up at the slightest hint of thirst. The message stuck. But the pendulum has swung so far that overhydration—also known as water intoxication or hyponatraemia—is quietly becoming a modern health concern. When you overwhelm your body’s finely tuned fluid balance, the consequences don’t simply fade with a trip to the loo. They can escalate, and quickly. More water is not always better. Understanding the early cues and the alarming red flags helps you stay safe, whether you’re training for a marathon, working through a heatwave, or just trying to live a healthier life.

What Overhydration Does to the Body

Your body relies on a strict equilibrium between water and electrolytes, with the kidneys acting as chief regulators. Drink significantly more than you excrete, and your sodium level becomes diluted. This matters because sodium helps control the movement of water into and out of cells. When blood sodium drops, water shifts into tissues. The result is cellular swelling that can affect every organ system. The brain is especially vulnerable because it is encased by the skull.

Early on, you may notice a heavy head, foggy thinking, or a queasy stomach. As hyponatraemia deepens, cells swell, pressure rises inside the skull, and symptoms intensify: pounding headache, confusion, unsteadiness, and, in severe cases, seizures. These are not hypothetical risks reserved for elite athletes. They’ve been documented in gym newcomers, festival-goers, and even office workers committed to “flushing toxins”.

Speed matters. A slow drift toward overhydration may produce subtle signs you shrug off; rapid overdrinking can cause abrupt deterioration. Medications that affect water balance—such as certain antidepressants or diuretics—can compound the risk. So can smaller body size, low-salt diets, and hot, humid conditions that nudge people to sip constantly. Recognising the trajectory early is critical.

Early Symptoms You Might Dismiss

Clues often start quietly. Crystal-clear urine, relentless trips to the toilet, waking at night to wee—these are common. Hands or ankles may feel puffy. Your ring fits tighter by evening. A dull, unshakable headache gathers behind the eyes. Some people report unexpected fatigue, a sense of heaviness in the limbs, or mild nausea after drinking large volumes quickly. These are not badges of healthy hydration; they may be warnings.

It’s easy to misread signals. Dehydration headaches often arrive with dry mouth, thirst, and dark urine. Overhydration-related headaches can occur despite pale or clear urine and frequent urination. Muscle cramps muddy the picture too: sodium dilution can cause cramping even when you’re “well hydrated.” Weighing yourself before and after long exercise helps; an overnight gain of a kilogram after a heavy drinking day hints at retained water rather than miraculous recovery.

| Symptom | What It Feels Like | Why It Happens |

|---|---|---|

| Throbbing headache | Pressure, heaviness, fog | Brain cells swell as sodium is diluted |

| Nausea/bloating | Queasy stomach, fullness | Excess fluid shifts into tissues and gut |

| Persistent clear urine | Frequent wees, day and night | Kidneys flushing surplus water |

| Muscle cramps | Tight, twitchy limbs | Electrolyte imbalance—not lack of water |

If several of these symptoms cluster after heavy drinking of plain water, consider easing intake and reassessing. Swap automatic refills for mindful sips, and observe whether the pattern settles over 24 hours. If symptoms persist or worsen, seek professional advice.

Red Flags Requiring Immediate Help

Some signs should set off alarms. Severe, escalating headache. Vomiting that won’t stop. Confusion, agitation, or difficulty speaking. Seizures. Shortness of breath or chest tightness after large fluid intake. These can indicate acute hyponatraemia, a medical emergency. If you witness these symptoms in yourself or someone else, especially after prolonged exercise or heavy water consumption, call 999. Do not delay. Rapid treatment to correct sodium safely can be lifesaving.

Who is most at risk? Endurance runners and hikers who drink at every opportunity. Clubbers or festival-goers using MDMA, which disrupts fluid regulation and can trigger compulsive drinking. Older adults or those with heart, kidney, or liver disease. People taking thiazide diuretics or certain antidepressants (SSRIs), which can impair the body’s ability to shed water. The common thread is impaired water clearance or behaviours that overshoot sensible intake.

When seeking help, tell clinicians how much and how quickly you drank, what the fluid was, and any medications or conditions. That timeline can point to hyponatraemia faster than any single test. If you’re uncertain but concerned—persistent headache, confusion, or repeated vomiting after overdrinking—call NHS 111 for guidance. Trust your instincts. Speedy assessment prevents complications, including dangerous brain swelling.

How to Hydrate Safely Without Overdoing It

Start simple: let thirst guide you in daily life. Aim for urine that’s a pale straw colour rather than crystal-clear all day. Eat your fluids too—soups, fruit, vegetables—and pair drinks with meals to support electrolyte balance. For long or sweaty sessions, include electrolytes, not just water. The goal is balance: replace what you lose, not everything you can carry. Beware of social pressure to “chug”; steady sipping usually serves you better.

During endurance exercise, practical ranges help. Many athletes do well with roughly 400–800 ml per hour, adjusted for body size, pace, and weather. Avoid routinely exceeding about 1 litre per hour, which raises the risk of dilution. Weigh yourself before and after long sessions; weight gain suggests overdrinking, while a small loss (up to 2%) is typically acceptable. Practise your plan in training, not on race day, and include salty foods if you’re a heavy sweater.

Special situations need tailored plans. If you’ve been told to limit fluids for heart or kidney problems, follow that advice strictly. Hot workplaces, pregnancy, and high-altitude trips all change needs. When in doubt, personalise hydration with a clinician, sports dietitian, or occupational health team. A few thoughtful habits—pausing to check thirst, glancing at urine colour, choosing drinks with minerals—protect you far better than counting bottles.

Overhydration doesn’t arrive with a siren; it creeps in through good intentions and misunderstood rules of thumb. Knowing the early signs and respecting the red flags keeps you on the right side of healthy. Balance, not bravado, is the mark of smart self-care. Think about your routines at work, at the gym, on nights out. What small, sustainable adjustments would help you drink more wisely this week, and which warning signs will you keep an eye on?

Did you like it?4.6/5 (25)